I got to thinking of the Zen masters, one old dog in particular. The one who said, “It’s your mind that’s troubling you, is it? Well then, bring it out, put it down here, let’s have a look at it!” (Henry Miller)

Rachael Cayley has a good post about academic writer’s block up at the LSE Impact Blog, citing Helen Kara and Julia Molinari as inspiration. I think we’re all more or less on the same page on this issue. “Writers block” is a false name for a real problem. When we “debunk” writer’s block we are not denying the experience it names, which is very real, and entirely unpleasant. We are simply proposing a less occult explanation for it than the one people who say they are “blocked” are invoking, sometimes unconsciously. We are not saying that things don’t go bump in the night. We are saying that your house is probably not haunted. Or at least not as haunted as you think.

When someone tells me they are blocked, I take the attitude of a parent dealing with the monsters under the child’s bed. Most importantly, I don’t participate in their fear. While the child’s mind is assembling the play of light and shadow and the creaking that the motions their own body makes in the bed into the shape of some horrid beast, I know what’s really down there — namely, nothing — and I am not afraid. The child learns from my reaction to the “signs” that they are not dangerous, just familiar indications of something much simpler, something harmless. An important part of the “exorcism”, of course, is to have a look. Perhaps with a flashlight, perhaps just by turning on the lights in the room. What we thought was a scary monster turns out to be a lost toy and an old sock.

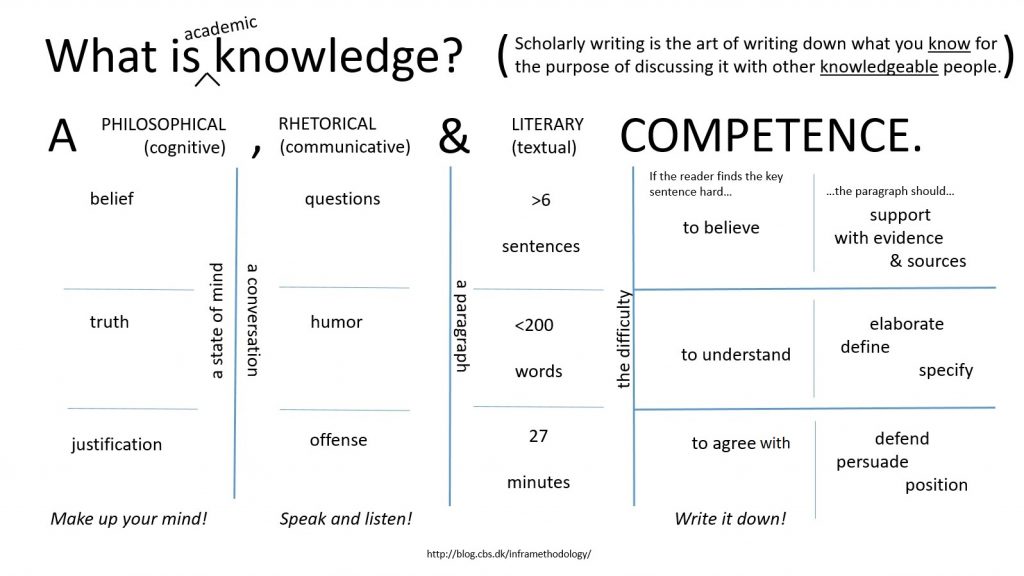

But how do we get a good a look under the bed of the writing process? How do we see that there’s nothing in the way of anything where the process is supposedly blocked. Well, the first question is: what is it you can’t write? What is it you think you should be able to say but can’t because your writing is stuck? At this point, the author will usually be able to identify the paper or chapter that is giving them trouble. That is, there is some specific text on which they are not making progress. And if I had probed them a little further, they would probably even be able to identify the intellectual difficulty they are facing. Sometimes, if I had in fact talked to them about it, they would have revealed that they didn’t have a clear idea of who their reader is. Both of these insights, of course, would immediately have revealed that the blockage isn’t really located in their writing, but in their thinking, their knowing. They are writing either about something or for someone they don’t know well enough. That’s the problem they’ll have to fix. (This is essentially Rachael’s cure for so-called writer’s block.)

But I don’t actually go down that route very often. Usually, I just ask them to identify the single paragraph they can’t write when they give themselves a moment to do so. This is sometimes puzzling to them. They’re happy to focus on a particular section of the paper, perhaps, but a single paragraph? They hadn’t considered the problem in those terms.

So I send them home with the following prescription: this evening, when you are done learning new things, done thinking about old problems, and ready to relax with a good book or a television show or the pleasant company of your friends or family, take five minutes to identify one thing you know that is of relevance to your paper. Formulate a simple, declarative sentence that states this truth. Ask yourself whether it’s something you need to tell your reader. If it is, ask yourself what difficulty it poses for the reader, why does it deserve a whole paragraph. (Is it hard to believe, to understand, or to agree with?) That’s it for today. Don’t spend more than five minutes on this. Just write the sentence down and consider the reader’s difficulty. Decide on a time tomorrow morning when you will spend 18 or 27 minutes writing a paragraph to support, elaborate or defend your sentence. Then get on with that relaxing evening I was talking about.

The next day, spend the planned 18 or 27 minutes working on the paragraph. When the time has run out, stop. No matter how well it went, stop. Stop even if you feel the block is gone and you’re elated and want to keep going. Stop even if you got no further than the sentence you already had the day before. So long as you faced the difficulty squarely at the time you planned, you have done what you could today. At the end of the day, make another plan for tomorrow. Write or don’t write three paragraphs this way in three days. Then come and see me again.

If you have done as I said, if you formulated three key sentences on three consecutive evenings and sat down the next day writing, or not writing, for 18 or 27 minutes, then you have, at least, taken a serious look at the problem you call writer’s block. You have probably also realized that you aren’t actually blocked. But in the unlikely event that you did no writing at all under these conditions — just sat in front of you computer watching the cursor blink — you at least have those three key sentences to talk to me about. Three different things you don’t know how to say. And we can talk about how to say them, and who to say them to. The experiment — the process by which you got the experience we can talk about — can have taken as little as a an hour altogether. If you still want to believe in ghosts and monsters and blocks after that, I can’t stop you. And I’m actually not sure I can help you either. I don’t think it’s your writing that there’s something wrong with.

(To be continued.)