I’ve been looking forward to this week. Today I will be holding my first writing workshop of the semester and tomorrow the Art of Learning Series begins. My theme this year will be “rebauchery” — a word I have made up to name the process of bringing meaning into our work, of taking our problems into the workshop (“bauche”, cf. “debauchery”). This will require us to find the pleasure in our labors, to discover the purpose of our studies. As always, I find my inspiration in the instructions of Oliver Senior and will try to help our students “acquire the mental equipment by which their vision may be directed, extended, and refreshed.”

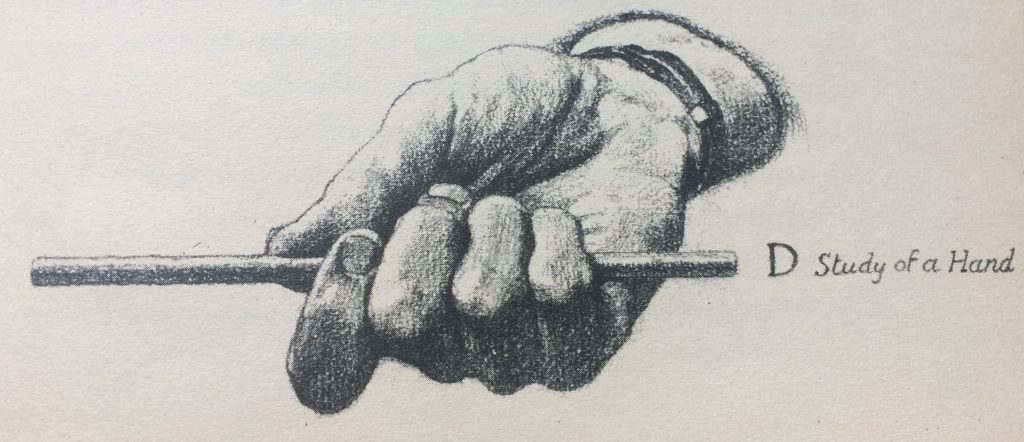

If you want to learn how to draw hands you will need to sit down at your desk, take out a piece of paper and a pencil, hold one hand steady in front of you, in a comfortable position, in good light, and look carefully at it. Then, with your other hand, pick up the pencil and begin to mark up the page in such way that it represents what is present before your eyes, namely, a distribution of light and shadow that is recognizable as your own hand. This is not easy and your first attempts will probably not be very satisfying. But if you want to become good at this you’ll just have to keep trying.

Now consider the problem of writing down your ideas. Here, again, you’ll need to get comfortable with the situation. You’ll need to hold an idea steadily before your mind’s eye and, well, be a little “bright”, light it up. (“When I’m writing a poem,” said Tony Tost long ago, “I’m basically just trying to be brilliant.”) Just as you wouldn’t try to draw a hand as it looks when you’re waving it around in the dark, you don’t want to try to write down an obscure idea that keeps changing the more you think about it. Don’t pick something you hardly know is true. Pick something you know comfortably and get to work on the other difficulty: the problem of writing. That’s what my writing workshops are intended to show you how to do.

We must retract our offerings, burnt as they are.

We must recall our lines of verse like faulty tires.

We must flay the curiatoriat, invest our sackcloth,

and enter the academy single file.

- Ben Lerner, The Lichtenberg Figures

To learn is to acquire new knowledge, to become knowledgeable — able-to-know and enabled-by-knowing. Though we say we “acquire” it, knowledge is not so much a possession as it is a competence. Knowledgeable people are capable of things — things they know something about — that ignorant people are not. Specifically, they are able to think about things, to talk about them, and to write them down. Students and scholars — academics, if you will — are more cognizant, more conversant, and more literate about their subjects than most people. Or that, in any case, is the ideal that guides our institutions of higher learning. On an average day, I am a defender, even a champion, of those institutions. I’m an idealist, let’s say.

My advice to students about how to get the most out of their education centers on those three basic skills: thinking, talking, and writing. But becoming good at these things requires us to consider some complementary ones: feeling, for example, and listening, and reading. So, in my Thursday afternoon talks, I will suggest ways to develop an academic comportment in our attempts to gain knowledge. After all, there are many ways of knowing and “academia” isn’t for everyone. Academic knowledge, we might say, is the sort of thing you can learn in school, and there are many things you very definitely can’t learn here. (Some would say there are things you positively mustn’t!) But there are also many things that can be imparted to you by way of books and lectures, and these things can be tested by way of writing and speaking. The gradual formation, and periodic examination, of your beliefs is what school is all about.

The last two talks are called “How to Enjoy Things” and “How to Know Things Again”. I’m looking especially forward to these talks because they introduce something that has occupied my mind this past year with increasing intensity. To be good at something is to be able to enjoy it. And if you have ever known something — I mean really known it — you know how to learn it (or similar things) again when you need to. You understand the discipline. You know your way around the workshop. And you can derive genuine pleasure from the work. That’s what I want “rebauchery” to mean.