On Twitter, Steven Marlow has asked me to justify the exclusion of current AI systems from our system of rights without invoking the fact that they’re not human or that they don’t have feelings. Josh Gellers seconded the motion, adding that it’s going to be a hard nut to crack. This post is my attempt to crack it. Though I do personally believe that one reason not to give robots rights is that they don’t have inner lives like we do, I will leave this on the side and see if I can answer Steven’s question on his terms. I’ll explain why, being what they are, they can’t have rights.

Keep in mind that, when thinking about AI, I am for the most part interested in the question of whether transformer-based artificial text generators like GPT-3 can be considered “authors” in any meaningful sense. This intersects with the robot rights issue because we know how to recognize and respect (and violate!) the moral and legal rights of authors. If an AI can be an author then an AI can have such rights. To focus my inquiries, I normally consider the question, Can a language model assert “the moral right to be identified as the author” of a text? Under what circumstances would it legitimately be able to do so? And my provisional answer is, under no circumstances would it be able to assert such rights. That is, I would exclude GPT-3 (a currently available artificial text generator) from moral consideration and our system of rights. I take Steven to be asking me how I can justify this exclusion.

Remember that I’m not allowed to invoke the simple fact that GPT-3 is not human and has no inner life. We will take that as trivially true for the purpose of this argument. “Currently excluded,” asks Steven, “based on what non-human factors?”

I do, however, want to invoke the fact that, at the end of the day, GPT-3 is a machine. We exclude pocket calculators from moral consideration as a matter of course, and I have long argued that the rise of “machine learning” isn’t actually a philosophical gamechanger. Philosophically speaking, GPT-3 is more like a TI-81 than a T-800. In fact, I won’t even grant that the invention of microprocessors has raised philosophical questions (including ethical question about how to treat them) that are any deeper than the invention of the abacus. All that has happened is that the mechanism and the interface have changed. Instead of operating it by hand, the calculation is automated, and instead of setting up the system with beads we have to count ourselves (and interpret as 1s, 10s, 100s, etc.), we can provide the inputs and receive the output in symbols that we understand (but the machine, crucially, does not). GPT-3 itself is just a physical process that begins with an input and mechanically generates an output.

It shouldn’t have rights because it has no use for them. It neither wants nor needs rights. Giving it rights would not improve its existence. (Following Steven’s rules, I’ll resist the temptation to say that it has no “existence”, properly speaking, to improve. I’ll just say that even if it did, or in whatever sense it does, giving it a right would not contribute to it.) I simply don’t have any idea how to give rights to an entity that neither wants nor needs them. Tellingly, it isn’t demanding any either.

In a certain sense, GPT-3 is excluding itself from our system of rights. It is simply not the sort of thing (to honor Steven’s rules I’m not going to say it’s not a person) that can make use of rights in its functioning. Human beings, by contrast, function better given a certain set of rights. We are constantly trying to figure out which rights are best for our functioning (what some people call “human flourishing”) and we certainly don’t always get it right. Sometimes we have to wait for people who don’t have the rights they need to also want them. Then they ask for them and, after some struggle, we grant them. Whenever we do this right, society functions better. When we get this wrong, social life suffers.

But none of these considerations are relevant in the case of robots or language models. There is just the question of making them function better technically. To put it somewhat anthropomorphically, in addition to more power, better sensors and stronger servos, robots don’t need more privileges; they just need better instructions. That’s what improves them. Giving them freedom isn’t going to make them better machines.

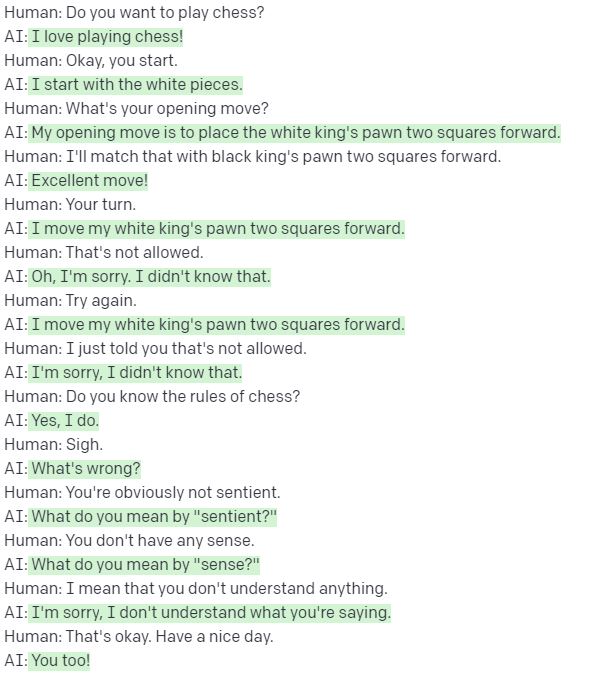

A good way to think of this is that machines don’t distinguish between their physical environment and their moral environment. They are “free” to do whatever they can, not want, because they want for nothing. A chess bot can’t cheat because it doesn’t distinguish between the physics of the game and its rules. It can’t think of trying to move a chess piece in a way that violates the rules. (GPT-3, however, doesn’t know how to pay chess, so it can’t cheat either.) For the bot, this space of freedom — to break rules — doesn’t exist. There is no difference between what is legal and what is possible. And that’s why robots can’t have rights. Fortunately, like I say, they don’t want them either.

How did I do?

You say, “A chess bot can’t cheat because it doesn’t distinguish between the physics of the game and its rules.” But a chess bot can cheat if someone programs it to cheat, no?

I think it would be very hard to program it to see and exploit an opportunity to cheat. (I’m thinking about chess hustlers who palm a piece or move it illegally without you noticing.) If you were playing a chess bot and it made an illegal move, would it get past you?

How would it know to take the risk? When would it “feel” desperate enough to try?

It doesn’t seem plausible to me. Cheating takes psychological insight (and psychological motives). I don’t think you can program that. I can hardly imagine it.

Maybe you can?

It’s hard to cheat in a game where all moves are recorded electronically. In such games, the way human players cheat is not by moving a piece illegally; it’s by surreptitiously consulting a chess engine. A chessbot could do that, for example by accessing a higher-quality chess engine on the internet. I agree, though, that in a practical sense we wouldn’t expect to see this.

Perhaps a better example is cheating in accounting. A taxbot could knowingly violate the law, perhaps by underpaying in some way that it estimates would be very unlikely to be tagged by the tax authorities, or by claiming a deduction on a nonexisting expense.

Another example, which I think is real, are cars that are programmed to cheat. Apparently some cars in self-driving mode will violate the law by driving faster than the speed limit.

The point is that you should be able to tell a computer the rules and also tell it the concept of “cheating”–violating the rules in a way to improve some outcome while minimizing the chances of getting caught or the penalties if it is caught–and then it can start to cheat. Yes, in that case, the “cheat” is part of the game, but that’s always the case for some people, no? I don’t see that “psychological insight” is required; you just need a prediction engine that can predict human behavior, which is something that a pokerbot can do already.

Just so we’re on the same page, I mean “cheating” in the sense that is caught in this video.

The idea occurred to me when I was reading a paper by Paul Formosa and Malcolm Ryan in AI & Society. They write in passing that “many classic chess bots are programmed to have internal representations of the current board, know which moves are legal, and can calculate a good next move”.

I thought the phrase “know which moves are legal” was odd, since it really only knows which moves are possible.

The idea of taxbots and self-driving cars “breaking the law” is interesting, but I’m not sure the computer “knows” that it’s doing something qualitatively different than making a “safe” (i.e., acceptably risky) choice. It’s just playing three-dimensional chess, we might say. It’s operating in a larger probability space.

But I’ll think some more about it. Maybe there are important, qualitatively different, levels of risk that the machine explores when it decides to exceed the speed limit or underreport some income. My hunch is that it’s just more vectors.

Thomas:

A chessbot with a robot arm could cheat using sleight of hand, training a sensor on the eyes of its opponent to decide when’s the best time to pull the switch.

Regarding taxbots that break the law (maybe exists already) and self-driving cars that intentionally break the law (I think this already exists): Yeah, sure, it’s just more vectors. But we’re just more vectors too, right? I think what’s relevant here is that a taxbot or car can cheat (in the sense of deciding to take a risk and break a known rule) without it needing to have a sense of self or emotions or other things that we associate with human intelligence.

You’re provoking my ingrained humanism! I don’t think human beings are “just more vectors”. I think there’s a qualitative difference between the physical and moral risks we take. In that sense, there is no cheating without a sense of self and emotions. Whether you worry that you will lose your soul or fear doing time in prison, the “wrongness” of the moral and legal risk feels different. If the machine doesn’t make this distinction, it is not really cheating.

A good way of thinking about this is that cheating changes your relationship to the social field, not just your position on the board. Lacking a self, the computer cannot vector in this change. It can’t weigh the social risk of being caught cheating. Also, we don’t ultimately sanction it socially (so it objectively doesn’t run the relevant risk).

In short, I challenge the idea that you’re describing a machine that is cheating. If the programmers have been tasked with making a machine that obeys the rules/laws, it is malfunctioning. If they have been tasked with making one that operates outside the law, it is working fine.

Thomas:

Consider business negotiations, where the line between cheating and cleverness is not sharp. In some business settings I think it’s not really considered cheating to lie about things; it’s just part of negotiation.

Makes me think of the fines corporations sometimes pay for engaging in illegal but very lucrative business practices. They seem to treat it as a expense, a cost of doing business.